How Do We Move More Patients to Peritoneal Dialysis (PD)?

Innovations in care delivery, surgical procedures and medical devices continue to improve the argument for PD.

TAKEAWAY: When patients have access to PD and are properly supported, they tend to live not just longer, but better. They regain routines. They regain energy.

A Kinder, Gentler Dialysis

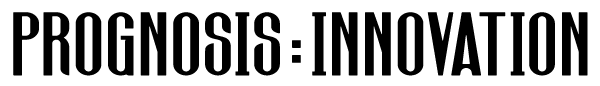

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) is a home-based therapy that uses the patient’s own peritoneal (abdominal cavity) membrane to filter waste and excess fluids from the blood. Unlike hemodialysis (HD), which requires a machine at a clinic and vascular access to circulate blood through an external filter, PD introduces a sterile dialysis solution into the abdominal cavity via a catheter. This solution draws out toxins and is later drained—typically multiple times a day (CAPD) or automatically overnight using a machine (APD).

The treatment can seem scary, as it requires the placement of a small port in the patient’s abdominal wall to enable fluid exchange. But that isn’t the biggest reason patients are under-prescribed PD as the preferred treatment option. Doctors have in the past been reluctant to promote the therapy due to perceived concerns about patient suitability or potential complications like eligibility and post-surgical catheter blockage.

However, advances in placement techniques such as laparoscopic insertion, omentopexy and improved patient selection protocols have addressed these issues, making PD a viable and reliable option for a broader range of patients.

For patients, PD allows for a gentle, continuous form of dialysis that patients can perform at home—often while sleeping. For many, this results in improved energy levels, fewer dietary restrictions and greater flexibility in daily life. For caregivers, PD is clinically appealing since it supports a preservation of residual kidney function, lowers hospitalization risk in the early years of treatment and avoids the complications associated with vascular access and large fluid shifts seen in HD.

Beyond the lifestyle improvements and clinical appeal, PD also delivers tangible economic and healthcare system benefits. Data from countries such as Hong Kong, Thailand, Chile, Canada, and New Zealand consistently show that PD can cost 20–40% less per patient per year than in-center HD, with no significant differences in survival when patients are appropriately selected. Hong Kong’s long-running PD-first policy, in place since 1985, supports more than 75% of its dialysis population on PD—saving millions of dollars annually. Thailand saw similar financial and equity gains after implementing its own PD-first initiative under the Universal Coverage Scheme in 2008.

In the United States, however, PD uptake remains under 15%, despite policy support from Medicare and the Advancing America Kidney Care Executive Order recognizing the benefits of home-based care. The reasons are complex, but the opportunity is clear: Increased use of PD can improve patient experience and quality of life while reducing costs at both institutional and federal levels.

PD can cost 20–40% less per patient per year than in-center HD

75% of dialysis population in Hong Kong uses PD, saving $Millions

Why Aren’t More Americans Using PD?

Insurance companies and the government would certainly prefer more patients choose that option. As mentioned, like their foreign counterparts, U.S. policy makers have implemented their own strategies to encourage uptake with a view to lower health care costs while maintaining quality of care. In 2011, the Medicare ESRD Prospective Payment System (PPS) introduced bundled payments for dialysis, making PD financially more attractive to providers. More recently, the ESRD Treatment Choices (ETC) model—launched by CMS in 2021—introduced performance-based incentives tied to home dialysis rates and transplant referrals.

These efforts are working, but slowly. National PD use increased from about 9% in 2010 to the current level of 15%—encouraging, but well below the rates achieved in other countries.

Why the gap?

Four major barriers explaining the underutilization of PD in the U.S.:

- Fear of infection. Peritonitis, a bacterial infection of the peritoneal lining, has long been the most cited complication of PD. While rates have dropped with better training and sterile protocols, the perception of risk remains a powerful deterrent.

- Fear of surgery or catheter placement. Many patients—and some clinicians—are hesitant about inserting a permanent abdominal catheter, especially in patients with prior abdominal surgery or obesity. Concerns about recovery, leaks, or catheter failure discourage referrals.

- Lack of education or awareness. Patients often start dialysis in an emergency and are placed on HD by default. Many report never being told that PD was an option. Clinicians may also lack training or incentives to initiate PD conversations early enough in disease progression.

- Catheter blockage concerns. Some surgical specialists—particularly those focused on the liver or abdominal organs—view PD as unreliable due to historical issues with the PD catheter blockage (particularly, the omentum – a fatty tissue layer in the abdomen) wrapping around the catheter. This perception, though often based on outdated techniques, still influences opinions.

Each of these barriers has a historical basis, but most have already been challenged—or even overturned—by clinical advancements.

Acknowledging Concerns and Solving Them

These concerns are real, and they do affect uptake. But nearly every one of them has a documented solution in current clinical practice.

- Fear of surgery

→ It can seem scary to have a port installed in your belly. But modern catheter placement is now often done laparoscopically, under local anesthesia, in an outpatient setting. Recovery time for first use has dropped to 3–7 days (as compared to multiple weeks with HD), and urgent-start PD protocols now allow for treatment to begin within 48 hours in qualified centers.

- Fear of infection

→ Peritonitis rates have fallen steadily due to better patient training, prophylactic antibiotics and advances in catheter design (see our focus on Lightline Medical below). Today, many programs report <1 episode per 24–36 patient months—well within ISPD safety benchmarks and nearly half the rate of CVC access (for HD). - Lack of education

→ CMS mandates that nephrologists discuss all modality options with patients. Programs like “Kidney Smart” and nurse-led pre-dialysis counseling have shown strong results in helping patients choose PD when informed. Some hospitals now automatically evaluate all eligible patients for PD before initiating HD. - Omental blockage

→ This was once a major cause of catheter failure. As recently as 2000 failure rates were as high as 30% and often required minor surgical intervention. But omentopexy (suturing the omentum away from the catheter) and pre-operative imaging have nearly eliminated this issue in centers using modern techniques. Surgical registries now report omental entrapment rates of <5%.

Catheter-associated infections—especially bloodstream infections from central venous lines (CVC) and peritonitis from PD catheters—remain a critical challenge for dialysis patients. These infections account for more than 40% of all hospital-acquired infection incidents and represent a leading source of morbidity, mortality and healthcare costs. They’re increasingly driven by antibiotic-resistant organisms, with standard prevention methods (sterile technique, alcohol swabs) clearly falling short.

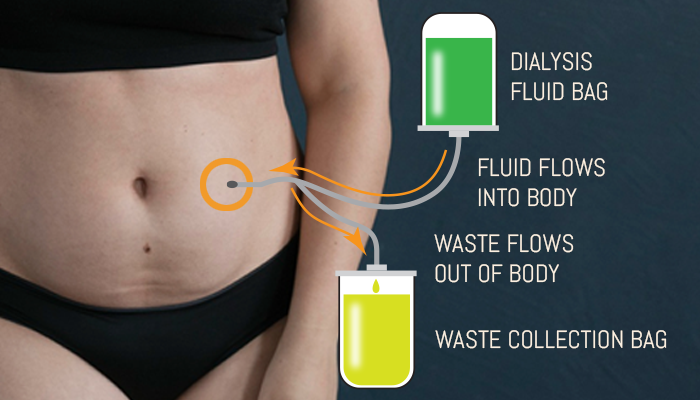

Light Line Medical’s PhotoDisinfection System delivers visible light via an integrated fiber-optic within standard catheter lumens—inside and out—to prevent biofilm formation and directly kill antibiotic-resistant bacteria and fungi. Unlike UV-based or chemical antimicrobial approaches, this solution is non-toxic, compatible with off-the-shelf catheters and relies on a safe mechanism (photodynamic disruption of microbial porphyrins) to achieve pathogen addressing the root cause of infection at the catheter interface—arguably the most vulnerable point in care environments.

Light Line Medical’s PhotoDisinfection System delivers visible light via an integrated fiber-optic within standard catheter lumens—inside and out—to prevent biofilm formation and directly kill antibiotic-resistant bacteria and fungi. Unlike UV-based or chemical antimicrobial approaches, this solution is non-toxic, compatible with off-the-shelf catheters and relies on a safe mechanism (photodynamic disruption of microbial porphyrins) to achieve pathogen addressing the root cause of infection at the catheter interface—arguably the most vulnerable point in care environments.

The company, under the management of CEO Vicki Farrar, has advanced rapidly from concept to near-commercial readiness: It secured intellectual property protection, gained early accolades (e.g., third place in Hangzhou’s innovation competition) and executed a know-how license with Mayo Clinic to enhance its platform’s scientific foundation.

Critically, the company has achieved >99.99% microbial kill rates confirmed by FDA‑certified labs. The results which are now being prepared for a U.S. 510(k) submission targeting PD catheters, will be followed by the company’s expansion into urinary and vascular catheters.

Thus far the company has executed a know-how license with Mayo Clinic for all four of its fields of use and performed simulated use studies with 32 PD patients in Mayo’s Florida clinic and DaVita’s clinics in the Northeast. Recently, LLM’s PD product was accepted into the FDA’s Safer Technologies Program (STeP), providing the company with an expedited 510k review process and a de-risked regulatory pathway.

Revisiting the Benefits: Why This Still Matters

Healthcare systems reap the rewards of lower system overhead, and individual practices can benefit as well, with lessened long-term health risks, lower costs per patient, decreased demand on dialysis clinics and improved access in rural and underserved areas. But for all the technical detail and clinical benefits, what ultimately matters is the experience of the patient living with kidney failure. And when we step back, the question becomes simple:

What kind of life does each option allow?

PD patients report better preservation of residual kidney function, fewer hospitalizations in the first year and experience fewer dietary and fluid restrictions than those on in-center HD.

Patient-reported Comparisons: Peritoneal Dialysis (PD) vs Hemodialysis (HD)

Offers more consistent daily fluid and electrolyte balance, resulting in fewer energy crashes. Patients typically feel more alert in the mornings.

Offers more consistent daily fluid and electrolyte balance, resulting in fewer energy crashes. Patients typically feel more alert in the mornings.

Energy and Fatigue

Many experience post-treatment fatigue or “dialysis fog,” making it difficult to resume activities after sessions.

Many experience post-treatment fatigue or “dialysis fog,” making it difficult to resume activities after sessions.

Typically involves fewer restrictions on fluids, potassium and certain foods. Patients enjoy more flexibility with meals and hydration.

Typically involves fewer restrictions on fluids, potassium and certain foods. Patients enjoy more flexibility with meals and hydration.

Dietary Freedom

Requires strict fluid, sodium, potassium and phosphorus limits. Many patients feel constantly thirsty or frustrated by food limitations.

Requires strict fluid, sodium, potassium and phosphorus limits. Many patients feel constantly thirsty or frustrated by food limitations.

Absence of post-treatment crashes improves sleep quality and emotional stability. Many report feeling more balanced day to day.

Absence of post-treatment crashes improves sleep quality and emotional stability. Many report feeling more balanced day to day.

Sleep and Mental Health

Sleep disturbances are common, especially after late-day treatments. Emotional lows related to exhaustion and fluid shifts are more frequent.

Sleep disturbances are common, especially after late-day treatments. Emotional lows related to exhaustion and fluid shifts are more frequent.

Fewer treatment-related interruptions allow patients to participate in social activities more freely. Can be integrated into daily household routines with minimal disruption, discreet equipment and improved privacy.

Fewer treatment-related interruptions allow patients to participate in social activities more freely. Can be integrated into daily household routines with minimal disruption, discreet equipment and improved privacy.

Lifestyle Flexibility

Fixed schedules and fatigue can reduce participation in work, social events and travel leading to reduced freedom and increased feelings of isolation.

Fixed schedules and fatigue can reduce participation in work, social events and travel leading to reduced freedom and increased feelings of isolation.

Improved Quality of Life

This becomes the most compelling case to patients for PD; it’s not financial or clinical, but returning to some semblance of normalcy while undergoing needed treatment is preferred. Humans don’t respond meaningfully to numbers and statistics. But they will respond when it’s personal. When patients have access to PD and are properly supported, they tend to live not just longer, but better. They regain routines. They regain energy.

In many cases, patients regain the sense that their illness, while serious, does not define them. And the regained sense of self-sufficiency opens doors they feared forever closed.

States one patient, “When I was on HemoDialysis I had one three-hour window after each treatment to try and get anything done. After that it was feeling miserable again until my next treatment, three times a week. The swings made me and everyone around me miserable. Now I just hook up a manual pouch a few short times during the day. I get to pick when and where that is, as long as there is about 90 minutes between them. That’s what is best for me.”

A system at rest stays that way unless acted upon by an outside force. The same is true for established care delivery “habits” and ingrained life lessons carried by practitioners.

Innovations are only the first step. Very often we must primarily address the patients’ “perception of risk,” but in this case educating professionals about recent advancements may be more useful. Our first goal needs to be increasing the education rate from a paltry 40% to something more in line with what other health systems are healthily achieving. By educating our peers and our patients on the benefits of PD and directly addressing the mistaken assumptions, we can promote its adoption as the standard of care.

For more information about improving awareness and education regarding PD, see our “Peritoneal Dialysis FAQs” and interviews with existing patients (coming soon).

#Dialysis | #PeritonealDialysis | #KidneyDisease